THREE DAYS OF

AUGUST

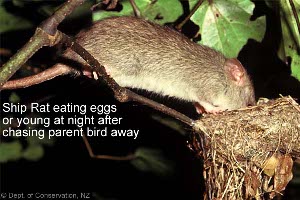

RATTUS RATTUS

During the 1950’s we lived in Rarotonga for five years but not once did we leave Rarotonga to visit other islands. We could not afford it on the small salary I was getting and besides travel by boat was the only means of visiting and this was a most uncomfortable affair.

In February, 1992, I returned to Rarotonga and between then and .June, 1994, I went to New Zealand several times, visited Tahiti and visited all of the Southern group of the Cook Islands and Pukapuka.

At a gathering held at my sister’s house in June, 1994, the discussion turned to visits around the islands and my wife stated “I haven’t been to any of them”. This statement decided me to take her to my father’s home island of Atiu during the school holidays in the first two weeks of August. We boarded the 20 seater Braemar Bandeirante aircraft fifteen minutes early at 12.45 p.m. on Saturday, 6th August. I had advised my wife to get the second seat back from the front but by the time we boarded there was no option but to take the very last seats at the back.

We have a full load of passengers. The forty-five minutes flight is uneventful except that below us there is a complete blanket of clouds and we cannot see any sign of the sea below. About ten minutes before landing there is an indistinct view of Takutea more from the line of breaking sea than from the land through the haze. Takutea was named by Mariri - the ancient ancestor of the Atiu people - when he caught a white fish here and exclaimed ‘Taku ku tea’ (My white ku). Takutea belomgs to the Atiu people but it is a reserve and a haven for fish and birds. Only scientific expeditions land here.

As we descend through the cloud layer I warn my wife that it is possible for us not to find Atiu or not be able to land because of the of the cloud cover and we could return to Rarotonga. There are a few bumps before we break through the clouds and there is Atiu ahead. As we get closer, the most prominent construction we can see is the Telecom dish and mast and the building. These are on a quarter acre of our land for which the rental is $100 a year. Telecom had offered 10cents a year, the land owners at the meeting stuck out for $100 and I told several of the relations that had I been there I would have insisted on no less than $2OOO as Telecom was a money making concern and not there for the benefit of the people even though they (Telecom) had made all sorts of promises. Telecom had offered to install a telephone free in each of the landowners’ homes. This-would be about 20 telephones.

There is a fairly heavy bump before a more gentle touch down. At the terminal I look out for Kura Malcolm but it is only Roger Malcolm I recognise. Kura is the daughter of Bill Allison who was Director of Education back in the 1940’s - 1950’s. Her mother is Atiuan. She is married to Roger and they run Atiu Villas. As she owns land and Roger has expertise in many areas it is an ideal set up.

Having established that we are his guests, Roger places an ei on each of about ten of us before we board his dual cabin utility truck with our luggage Roger tells us he will take us over a back road “because the motorway will be busy”. This remark gives me an insight to his sense of humour.

As we bump over the rough road between trees and outcrops of coral Roger gives us a few facts about the topography. Atiu is a volcanic island pushed out of the sea a million years ago so the centre is a plateau of volcanic soil. Surrounding this plateau is the lowland which was once the lagoon. Here is where crops of taro, puraka, taro tarua, maniota and bananas are grown. There are also mango, coconut and breadfruit trees. Surrounding the lowland is a slightly raised area which was once the reef. This is the makatea - an area of hard, sharp, brittle coral that is no good for cropping but amongst which coconuts, pandanus, wild hibiscus, tamanu, creepers and many native plants grow. In this area are the caves visitors are soon told about. The very outer rim of the island is the ledge of reef over which the waves continuously break. There is no lagoon. We drive upwards past a coffee plantation. This belongs to a German who has established a business here growing and producing the well known Atiu Coffee. We reach the plateau and drive along one of the five roads radiating from the centre of Atiu. Many years ago the missionaries had convinced the Atiuans that they would be safer from raids if they lived together in the centre of the island so here is found the people of Atiu - just over 1000 of them -living in five villages with a village along each of the five roads.

We come in from the north-west end of the settlements and our motel is at the very south-east end so we must drive through the centre of the island. First we pass the school - pre-school, primary and secondary - which like many schools in these islands is placed well away from the centre of town. This may be because of space, it may be because of the peace and tranquility the area offers or it may be to place children and teachers ‘out of sight, out of mind’. There is no school at this time so there is plenty of peace and tranquility.

Most of the roads are dirt but near the centre area some tar sealing was laid many years ago. The seal is very thin and there are numerous pot holes. We pass the large C.I.C.C. church with its impressive four foot (600mm) wide walls of lime. All is painted white - the church,the graves, the roadside wall. Just past the church, on the very edge of the tar seal is a large slab of lime about 1.2 metres square and rising to a peak about 2 metres into the air. This marks the supposed centre of Atiu. It has caused several accidents and Roger wonders why it has not been shifted. In the days of the missionaries much limestone was heated in huge ovens to turn it into soft, white, malleable lime from which many constructions were made. It was also used for painting the finished construction. We pass the settlements and finally arrive at our destination. We have marveled at the small number of people we have seen. Polynesians are not indoors people unless television will change all that and so I must assume they are all at their plantations.

At the Atiu Villas we dismount onto the red, dry, dusty clay. There is much of this about up here and anything white soon attains a pinkish tint. Kura and Roger tell us that they have a problem. They are overbooked. “Would you two stay in our house with us?” This suits me fine. It will give me a chance to know them better and also I am not sure of the food situation. Kura tells us she will supply us with food as compensation. There are four bungalows and there is also a house located a kilometer away from the Villas. The rest of the guests are taken by Roger to their respective accommodation while Kura takes us to their house and settles us in the room belonging to their two grown teenagers who are in schools in New Zealand.

Roger joins us for a cup of coffee and biscuits and then we are asked to join them at lawn bowls. There is a beautiful lawn tennis court on which they play bowls. The grass and worm mounds do not make for good bowling but this gathering is purely social and no one worries too much a bout the outcome. Playing bowls are the medical officer and her husband who both look like Pakistanis with names to suit. There are two New Zealand V.S.A. teachers. There is a local female school teacher who was at Teachers College last year, there is a young Caucasian who seems to be husband, Roger, Kura and ourselves making two teams of five. I played bowls one afternoon about twenty years ago in Kaitaia and know only the rudiments of the game but I enjoy the time with this group and get to know the New Zealand teachers fairly well as we share common knowledge of’ some places and some people in New Zealand. One Ron Dobbs - knows all the places I had taught in and as well he had done a good deal of traveling around the world. On one side of the tennis court is a large thatched house in which there are tables and seats, a bandstand, a tennis-table table and a bar. Roger gets us drinks all round for which we pay later. There are cans of beer at $3, bottles at $5, soft drinks at $1.50 and spirit: at $2.50 for single and $3 double. There was much talk of ‘ratting’ which was to take place at 5 p.m. but at 4.40 p.m. the score is 20-6 (our team has 6) and someone decides the winners must get 21. By 6 p.m. the winners finally get their 1 point while we had built up our score to 16. By this time it is too late to go ‘ratting’ so we sit down for a few more drinks before everyone disperses. We shall go ratting tomorrow. We sit down to a meal of roast lamb, potatoes, taro and beans but I was offered rukau and pork which Roger claimed was supposed to have been his but which Kura tells him he did not want. At about 8.30 p.m. We troop off to the bar where the band is in full swing but there are only men there. All the women are in Rarotonga. I had expected to see one or other of my nephews there but by 10.30 they have not come so we take ourselves off to bed.

Sunday 7th August

My wife would only go to the Catholic church which we were told would begin at 10 a.m. At 9.20 a.m.we are told the service started at 9 a.m I suggest attending the C.l.C.C. church but this is declined. I had wanted to hire a scooter but this is not available, however we are offered the motel vehicle - dual cab utility - on which we make a quick visit to two grave sites and the wharf and are back at the Atiu Villas by 11 a.m.as I am to join a group walking to Ana Takitaki in which lives the very rare Kopeka unique to Atiu. I am very interested in this visit because my grandfather had composed a very moving tale in poetry about this cave.

At 11.30 we are assembled around the utility and our guide, Kau Henry, introduces himself. We are taken by Roger part way on his utility and are then told it is a three hour round trip. After ascertaining there are twelve of us we set off, falling into single file later as we enter the makatea and the track becomes narrower. There is need to watch where one puts ones foot as the track is rough with sharp coral limestone jutting out everwhere ready to catch.an unwary foot and trip one over. There is a pause as Kau breaks open five candlenuts, threads them on a kikau and explains their use as candles. I am sad that he does not expound further on the candlenut - that the threaded nuts are dried in the sun before being used as candles, that the smoke given off helps to keep away mosquitoes, that the carbon collected from the smoke is used for tattooing, that the nut is a most extremely effective laxative, that the oil of the dried nut is used on weapons and ornaments, that the leaves are used as darts by children, that the wood is absolutely useless for anything. Short stops to expound the virtues or otherwise of the many native plants could make a walk so much more interesting and informative. There is very much to tell about the coconut, the pandanus, the ti, the nono, the tamanu but unhappily our guide does not speak about any of them.

After about an hour’s walk we arrive at the cave mouth and I am pleased to note the picture I’d formed from my grandfather’s poem fits in with fact. There is a more or less circular opening about seven to eight metres across. The floor is about five to six metres down and growing upwards from the centre of this is a tree - though not tamanu - and there is a branch down which one could descend though we descend over the rim. There are coconut trees around the edge of the cave mouth and in the cave mouth are coconuts.

We enter a darkened portion before coming to a bigger opening where again there is a tree growing upwards - much larger than the one in the first opening. There are impressive formations of stalactites. As we enter a tunnel, we are advised to use torches of which there are about six brought by guests from the cabins. The tunnel is about a hundred metres or so. But for the glimmer of torches it is dark. One must choose ones footing carefully or suffer a slip or a fall.

There are sharp outcrops of rocks from all angles and one may bang ones head or suffer a graze. One must be quick to catch a glimpse of where to put ones foot. There are holes one could slip into and there is moisture underfoot. We come into sunlight and walk along a rock face with most interesting stalactite formations on the rock face. Around the bend is a large opening we must enter. In here, in the dark of this cave, sleeps and nests the only existing kopeka. During the day they are out hunting for food but return to the cave during the evening and find their way in amongst the rock formations in absolute darkness.

Before we enter there are magnificent formations to look at. There are impressive stalactites hanging from the roof and lapping over the walls, some looking like hands, like flowers, like leaves. There are columns - some broken - and I cannot help thinking of the beautifully formed columns used as garden edging at the home of Queen Rongomatane. It is not so long ago that everyone would consider it a marvelous feat if a group of men broke off one of these and carted it back to the village. I do not know what steps if any have been taken to preserve what we now have of nature’s marvels. The columns at the queen’s home have been carted there by warriors of days that are not very long gone.

There are stalagmites jutting up from the floor, many of them showing their wet domes where a mixture of water and limestone is still slowly dripping and building the column up. Most interesting of all are the rosette edged tray forms on the cave floor. There are several of them among the columns and budding stalagmites and they are filled with water looking very much like large, shallow, fancy trays filled with water. How these began is difficult to imagine but it is obvious that once a rim is formed, the drops splash water and limestone onto the rim. The water on the outside of the rim evaporates leaving the limestone to add to the tray’s edge.

The next part of our journey is more hazardous and we progress slowly with our guide occasionally stopping to help people over the more difficult parts. After a half-hour’s walk we stop. All torches are turned off and we are made aware of the total absence of light in which the kopeka must find its nest and its young. We know they come here because there are the white splashes of their droppings on the rocks. To go further is too difficult and our guide tells us about three miles away is the sea. He could get there but he will not take visitors. We are told to go back and the fellow behind me immediately takes a wrong turn and our guide must once more assume the lead.

When we emerge into daylight again we are recommended to take a brief rest and our guide tells us the story of the cave and it’s naming.

I had stated that I would tell my tale of the cave when we reached its mouth with the opening and the tree there but now all I do is embellish the tale told.

On our way back through the makatea I expected our guide to talk about the various plants and trees but to my disappointment he does not. There is ti, nono, pandanus, tamanu, candlenut, hibiscus and numerous other plants.

As we begin our climb to the plateau he climbs a low coconut tree for drinks all around, and informs us that we shall be visiting the famed “Tumunu” of Atiu. It is about twenty minutes later that we reach this famed spot. There is a low thatched lean-to with a floor of concrete of about thirty square metres. There are eight men in a circle, two nursing a ukulele each, one with a guitar and one fellow, who was barman at the Atiu Villas and apparently brother to our guide, with a black, twenty litre, plastic barrel in front of him. In the old days before plastic was the biscuit tin and before the biscuit tin was the barrel carved out of the trunk of the coconut – tumunu - hence the name of this place. We are invited to sit. With a small, black coconut cup, the fellow with the barrel digs into the barrel and hands a small cupful to each of us in the now enlarged circle.

The same cup is used for everyone. It is courtesy to accept though I dread to think what the visitors think of hygiene. We are being given a taste of the local home brew beer. With our visit, the musicians have fallen quiet so I offer my rendering of a local song possibly to the surprise of the party - and our hosts join in. This has broken the ice. The cup goes the full circle twice and a third time and a fourth before I decline more but I have started them on three songs and played the ukulele for them and can depart with dignity. However, we must wait for Roger who thankfully arrives on cue. He joins us briefly and must have a taste of the brew before he can take us home though through courtesy we are expected to make a donaton to our hosts with which courtesy two of us comply. At the motel there is a little bit of fuss in paying our guide. A couple of times during our walk I had asked how he was paid and he was very evasive. Here, I ask Roger how much we are to pay and he says $6, which Roger assures us is on the circular in the cabins. However, the guide is asking $9.00 each, which annoys Roger. I have given Roger $6 and he waves away any more saying the guide cannot raise his charges without any warning. Later, we discuss this matter and realise at $6 a head he would have made at least $72 for 3 1/2hours work which is much more than he would have got from his weekly wages from the Ministry of Works.

At home there is a quick lunch and it is not long before Roger invites me to go ratting. I see a couple of cartons of rat traps in the ute and realise we are into the serious business of catching rats.

Roger is anxious to introduce to Atiu the Red lorikeet. It has beautiful red, yellow and green feathers, which could be used in decorations. However, these birds, their eggs and young are prey to ships rats or rattus rattus, but quite safe from the native kiore, the Pacific rat or the large Norwegian rat. We are on our way to trap as many rats as we can in a scientific means to establish whether or not there is any of rattus rattus in Atiu.

From the centre of town we pick up Ron Dobbs, one of the V.S.A. teachers and companion of the previous evening’s bowls, then head for the school. Roger splits a coconut, gets out the kernel which we cut into 10 X 15 mm blocks then bait ten traps each which we are to set at various areas indicated by Ron around the back of the school. They are to be set in pairs a metre or so from one another. Having set those we head back past the motels down to the taro swamps. Here we are directed to various areas - Roger upward of the road, me along the swamp and Ron also along the swamp.

From here we head back past the motel and turn a sharp right to the chicken farm where we set the last of the traps making about 96 in all, and making sure here to hide them from the chickens which are still wandering around. During all of this we have had a young six year old Miss accompanying first one then the other of us.

Back at the motels all seven of us cram into the tiny kitchen/dining room. Roger serves drinks all round and later we have a meal of casseroled chicken. When the men and the young lady leave - Roger to take the others home - I get myself a shower and into bed.

Monday 8th August.

At 7 am Roger and I pick up Ron and head back to the chicken farm where there is a very poor catch of about four rats from 26 traps.

Ron is pleased to see no fowl wearing a head band of a rat trap. Roger is relieved to get this part of the exercise over as he had arranged with the owner to allow us to trap rats here and any mishaps with the chickens would be on his head. From here we go to the school. Roger gets no rats on his traps but we are all saddened that on his second to last trap there are two beautiful black chicks - both dead. The point of catching two at once is mentioned several times later

I am sure to the embarrassment of the trapper concerned. There is recording taken on every trap set as to whether trap is still set with bait, set with bait missing, sprung with bait intact, sprung with bait missing, trap set off with catch of rat or other.

I do not know what is recorded for two dead chicks. I have better luck with my traps catching four rats from ten traps. We have difficulty finding two of Ron’s traps but get one only rat from his ten traps. Ron is knowledgeable, well traveled and precise in what he does but he acts and talks quickly as though giving no thought to what he is doing. This appeared to be the case when bowling and this appears the case with the traps and we must look for some of his traps.

Down at the taro swamps we first deal with Roger’s traps, which produce one rat and several crabs. There was a concern that these were coconut crabs but then Ron assures us they are not. We attend to my traps, which produce three rats and a couple of crabs. It is difficult to remember in thick bush just where one has put something especially when there are ten of them and I must search for some of my traps. When it comes to Ron’s traps however, Roger and I are very amused when he calls out “I can only find two”. We go to help him and finally locate them all though from what happened later. I am not sure we did locate them all. Pigs have rooted around these trees for very many years and I am entranced by the root formations. They twist and turn and curl over and under. There are loops, circles, elbows and knobs. Many of these forms would be useful adjuncts to my creations back in Rarotonga. In total we have caught fourteen rats, two of which I would have called mice but which Ron assures me are the native kiore, and the rest of them all about four times the size of the kiore. Some are wet and two or three are mutilated. All in all, not a pleasant sight.

Back at Ron’s place we all wash hands and wait for Ron and his brother Rex (?) to get us breakfast of coffee and toast. The men are leisurely over their breakfast and have a more leisurely second cup of coffee.

Then Roger tells me the next part of the job is the one they don’t savour _ not that any of it is savoury - and invites me to have a second cup of coffee.

We finally move to the outer room where our rats are in a carton. First Ron tells me to record, then sadly changes his mind. He will record. I will weigh and Roger will measure. When it comes to professional people working together one person assumes leadership and sets tasks and there is never any arguing. Each rat must be untangled from the others, hooked under a front leg by the hook on a spring balance and weighed, the weight recorded then the rat handed to the next person to measure. Ron is sure all our bigger rats are the Pacific rat and the two small ones are the native kiore. The first Pacific rat weighed 172 grams. Now measurements must be taken - from tip of nose to base of tail, from base of tail to tip of tail, length of right ear, length of right back leg, whether or not it has a dark strip along the top of the measured leg, whether male or female, distance from urethra to anus, if female whether vagina is open or closed, number of teats on chest, on abdomen? In all, a most unpleasant task but this is a scientific exercise and everything must be done carefully and precisely and the results recorded accurately. I can see Why the men did not approach the job with enthusiasm. Our first kiore weighed 65 grams. The gender of one small rat cannot be established as it is a very young one so Ron has to operate and finds two testes but as it is so young we cannot accurately classify it so it must be frozen and sent to Gerald McCormick in Rarotonga. Part way through our weighing and measuring our young companion of the previous evening together with her brother arrive and watch the operation. They are very anxious to take each a rat to their father with which desire the men are enthusiastic to comply. I had expected to be back home by 9 a.m. but it is 10 a.m. when Ron buries our catch in his vegetable garden and Roger and I are free to return home.

I wish to go and clean around and paint the monument to my father and may take the ute but when I have to wait for a family of German man and wife who have a teenage boy and girl of Indonesian descent whom they have adopted. They are going for a walk and wish to be dropped off at the other end of town. They take some time in corning and when they do the man is very apologetic and I can see the teenagers are not happy. I wonder if they realise how fortunate they are to be adopted and to escape the atrocities rampant in their home. They probably have no parents living and probably know no living relatives. When I drop them off, the lady, on the ground, asks the lad, still on the truck, to hand over a bag which he passes over and drops at her feet before she has time to hold it. Poor kids! and poor couple. I hope relationship is only like this on very rare occasions.

At the gravesite there is very much growth - two years of it - though it is obvious someone has been there during that time. The cursed albizia is what bothers me, and one, up against the concrete slab and about eighty millimeters through, had been cut down, sprouted two new shoots which have been cut again. I will not be able to kill it. There are others growing around most profusely. I ringbark many of the bigger ones and chop down the smaller ones. There are plenty of creepers and lantana with a few guavas but they are not much problem and I swing in with a machete that Roger has permanently in his ute. I am delighted to find all the plants we had put in two years ago are growing healthily. There is a bird’s nest fern (kota’a) at each corner of the monument. Two metres in front is a coffee plant now about 1.5metres high. About 5 metres on either side is a tamanu - one about 1 metre high and the other a little higher. As I must be back at the Atiu Villas by 1 p.m. I have not the time to paint. By 12.40 p.m. I have exposed all the plants to the sunlight and cut a new track to the road. Roger must go to meet the plane and I am back at the motel at four minutes to one. Later in the day I am able to have a motor scooter and go off to paint. I am able to paint my father’s monument and have half a litre of paint left to do a make-do job on the graves of my uncle and his wife situated near the football field about a kilometer away. The concrete on my uncle’s grave is very porous and a four-litre tub of paint would be required to do the job properly.

Back at the Atiu Villas I find we have been shifted to cabin 3. The cabins are very compact - high peaked wooden tile roof, which keeps the cabin cool during the heat of summer. Except for the tiles all the timber is local. Roger operates a sawmill and there is mango, coconut, albizzia timber in abundance. Roger has been extremely busy. He has put up all the buildings, with local labour no doubt, made all the furniture and laid all the paths and tennis court. In the cabin is a well stocked ‘fridge with a dozen cans of beer, cans of lemonade, U.H.T. milk cartons, butter, cheese and one or two other things. In the cupboard are cans of corned beef and cans of vegetables. On a shelf are bottles of various spirits. We are to record what we use and pay before we depart. There is a shower room, toilet and very small hand basin. Over the shower room is sleeping space for two - with mattress. There is a ladder. There is a gas stove with pots and pans also cutlery and plates, cups and saucers, and glasses. There is a double and a single bed with towels, which seem to be washed every day. There is a dining table with two chairs. The floor is wood with lino. The lower walls are coconut wood while the upper half is lined with pandanus matting with local paintings here and there. The back wall is a sliding door and glass with drapes. The sliding door lets one out onto a porch on which is a barbecue table. The porch overlooks a sloping lawn and out there is a large barbecue area with barbecue all set for anyone wishing to use it and there are concrete tables and seats of Roger’s own design and manufacture. The three posts on the outer edge of the porch are coconut trunks. I wonder how long they last. We would have had to get our own tea tonight except that Mataki’s son and the fellow’s wife and his aunt’s Rima and Kato have asked us out to their place for tea.

At 4.30 p.m. Roger and I pick up Ron and Rex and we head off for the school to set our traps. Rex is to accompany me to find out where my traps are as this could be my last trip. We head for the taro swamps and set those and as we pass the motels and it is nearly 6 p.m. I ask to be excused and Ron remarks “Bill, I didn’t think you were a piker!”

By 6.20 p.m. we are at the Kaiaruna home. The two ladies - Kato and Rima - are my cousins, their father Kaiaruna being my uncle. There is a table piled with food chicken, chop suey, poke, taro, maniota, kumara and rukau. After a brief chat we are invited to eat and I ask that all of us eat. Polynesian custom dictates that the hosts eat only when the guests (manuiri) have finished but I am hardly manuiri here and I am pleased when everyone eats. I try to eat as much as possible to show my appreciation only to suffer a little discomfort during sleep with a very full stomach. Tupu, Mataki’s son, is off to fish so does not join us at the meal but we have a very pleasant chat before my wife and I return home and I’m in bed by 9 p.m.

Tuesday 9th August

I am up at 6.50 a.m. and waiting in the truck at 7.10 am when Roger arrives. He is immensely amused to see me there expecting me to stay in bed as it is my last morning here. We pick up Ron and Rex and head for the chicken sheds. They have set twenty traps inside and we have a very good catch of about 18 rats. No trap is unsprung but a couple are empty. In another shed we collect another two rats.

We head for the swamps where we find most of Roger’s traps with crabs, one still alive with shell but there are no rats. Again we have much trouble with Ron’s traps having to hunt for all but the first two. There is one rat and several crabs. Four of mine also are not easy to find and again there is one rat and a couple of crabs. The last trap however has the front paw of a rat and Ron is sure the rat had chewed its own paw off so it could escape though I’m inclined to think the rat was eaten by other rats or crabs. My grandfather’s family emblem is the three legs of ancestor father and two sons who had severed their chained legs so they could escape from capture. Seeing this remnant of a leg reminds me of the family emblem. There will be a lot of rats to weigh and measure this morning and there are some ribald comments when I ask to be dropped off before this part of the operation.

After a breakfast of coffee and toast my wife and I mount a scooter and go off to take photographs at the monuments I had painted.

At about 1.15 pm about ten of us board the heavily laden utility and drive off to the airport with Roger taking a couple of new roads. At the airport Tupu gives me a cooked crayfish to take home. We have four cartons as well as our bags, a clock and two photographs, with us. Our luggage weighed well over our allowance. There is a fully laden plane, which is in the air by 2 pm We land in Rarotonga on time at 2.45pm.

Good, faithful Norman is there to take us home.

xxxxxxxxxxxxx